Interpretations of quantum mechanics

| Quantum mechanics |

|---|

|

| Introduction Glossary · History |

|

Background

|

|

Fundamental concepts

|

|

Formulations

|

|

Equations

|

|

Advanced topics

|

|

Scientists

Bell · Bohm · Bohr · Born · Bose

de Broglie · Dirac · Ehrenfest Everett · Feynman · Heisenberg Jordan · Kramers · von Neumann Pauli · Planck · Schrödinger Sommerfeld · Wien · Wigner |

An interpretation of quantum mechanics is a set of statements which attempt to explain how quantum mechanics informs our understanding of nature. Although quantum mechanics has held up to rigorous and thorough experimental testing, many of these experiments are open to different interpretations. There exist a number of contending schools of thought, differing over whether quantum mechanics can be understood to be deterministic, which elements of quantum mechanics can be considered "real", and other matters.

This question is of special interest to philosophers of physics, as physicists continue to show a strong interest in the subject. They usually consider an interpretation of quantum mechanics as an interpretation of the mathematical formalism of quantum mechanics, specifying the physical meaning of the mathematical entities of the theory.

Historical background

The definition of terms used by researchers in quantum theory (such as wavefunctions and matrix mechanics) progressed through many stages. For instance, Schrödinger originally viewed the wavefunction associated with the electron as corresponding to the charge density of an object smeared out over an extended, possibly infinite, volume of space. Max Born interpreted it as simply corresponding to a probability distribution. These are two different interpretations of the wavefunction. In one it corresponds to a material field; in the other it corresponds to a probability distribution — specifically, the probability that the quantum of charge is located at any particular point within spatial dimensions.

The Copenhagen interpretation was traditionally the most popular among physicists, next to a purely instrumentalist position that denies any need for explanation (a view expressed in David Mermin's famous quote "shut up and calculate", often misattributed to Richard Feynman.[1]) However, the many-worlds interpretation has been gaining acceptance;[2] a poll mentioned in "The Physics of Immortality" (published in 1994), of 72 "leading cosmologists and other quantum field theorists" found that 58% supported the many-worlds interpretation, including Stephen Hawking and Nobel laureates Murray Gell-Mann and Richard Feynman.[3] Moreover, the instrumentalist position has been challenged by proposals for falsifiable experiments that might one day distinguish interpretations, e.g. by measuring an AI consciousness[4] or via quantum computing.[5]

The nature of interpretation

What interpretations are interpretations of is a formalism — a set of equations and formulae for generating results and predictions — and a phenomenology, a set of observations, including both those obtained by empirical research, and more informal subjective ones (the fact that humans invariably observe an unequivocal world is important in the interpretation of quantum mechanics) . These are the more-or-less fixed ingredients of an interpretation. The ingredients that vary between interpretations are the ontology and the epistemology, which are concerned with what, if anything, the interpreted theory is "really about". The same phenomenon may be given an ontological reading under one interpretation, and an epistemological one under another. For instance, indeterminism may be attributed to the real existence of a "maybe" in the universe (ontology) or to limitations of an observer's information and predictive abilities (epistemology). Interpretations may be broadly classed as leaning more towards ontology, i.e. realism, or towards anti-realism.

Some approaches tend to avoid giving any interpretation of phenomena or formalism. These can be described as instrumentalist. Other approaches suggest modifications to the formalism, and are therefore, strictly speaking, alternative theories rather than interpretations. In some cases, for instance Bohmian mechanics, it is open to debate as to whether an approach is equivalent to the standard formalism.

Problems of Interpretation

The difficulties of interpretation reflect a number of points about the orthodox description of quantum mechanics, including:

- The abstract, mathematical nature of that description.

- The existence of what appear to be non-deterministic and irreversible processes.

- The phenomenon of entanglement, and in particular the correlations between remote events that are not expected in classical theory.

- The complementarity of the proffered descriptions of reality.

- The role played by observers and the process of measurement.

- The rapid rate at which quantum descriptions become more complicated as the size of a system increases.

Firstly, the accepted mathematical structure of quantum mechanics is based on fairly abstract mathematics, such as Hilbert spaces and operators on those spaces. In classical mechanics and electromagnetism, on the other hand, properties of a point mass or properties of a field are described by real numbers or functions defined on two or three dimensional sets. These have direct, spatial meaning, and in these theories there seems to be less need to provide special interpretation for those numbers or functions.

Furthermore, the process of measurement may play an essential role in quantum theory - a hotly contested point. The world around us seems to be in a specific state, but quantum mechanics describes it by wave functions that govern the probability of all values. In general, the wave-function assigns non-zero probabilities to all possible values of any given physical quantity, such as position. How, then, do we see a particle in a specific position when its wave function is spread across all space? In order to describe how specific outcomes arise from the probabilities, the direct interpretation introduced the concept of measurement. According to the theory, wave functions interact with each other and evolve in time in accordance with the laws of quantum mechanics until a measurement is performed, at which point the system takes on one of its possible values, with a probability that's governed by the wave-function. Measurement can interact with the system state in somewhat peculiar ways, as is illustrated by the double-slit experiment.

Thus the mathematical formalism used to describe the time evolution of a non-relativistic system proposes two opposed kinds of transformation:

- Reversible transformations described by unitary operators on the state space. These transformations are determined by solutions to the Schrödinger equation.

- Non-reversible and unpredictable transformations described by mathematically more complicated transformations (see quantum operations). Examples include the transformations undergone by a system as a result of measurement.

A solution to the problem of interpretation consists in providing some form of plausible picture, by resolving the second kind of transformation. This can be achieved by purely mathematical solutions, as offered by the many-worlds or the consistent histories interpretations.

In addition to the unpredictable and irreversible character of measurement processes, there are other elements of quantum physics that distinguish it sharply from classical physics and which are not present in any classical theory. One of these is the phenomenon of entanglement, as illustrated in the EPR paradox, which seemingly violates principles of local causality.[6]

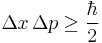

Another obstruction to interpretation is the phenomenon of complementarity, which seems to violate basic principles of propositional logic. Complementarity says there is no logical picture (one obeying classical propositional logic) that can simultaneously describe and be used to reason about all properties of a quantum system S. This is often phrased by saying that there are "complementary" propositions A and B that can each describe S, but not at the same time. Examples of A and B are propositions using a wave description of S and a corpuscular description of S. The latter statement is one part of Niels Bohr's original formulation, which is often equated to the principle of complementarity itself.

Complementarity does not usually imply that it is classical logic which is at fault (although Hilary Putnam did take that view in his paper "Is logic empirical?"). Rather, complementarity means that the composition of physical properties for S (such as position and momentum both having values within certain ranges), using propositional connectives, does not obey the rules of classical propositional logic (see also Quantum logic). As is now well-known (Omnès, 1999) the "origin of complementarity lies in the non-commutativity of [the] operators" that describe observables (i.e., particles) in quantum mechanics.

Because the complexity of a quantum system is exponential in its number of degrees of freedom, it is difficult to overlap the quantum and classical descriptions to see how the classical approximations are being made.

Problematic status of interpretations

As classical physics and non-mathematical language cannot match the precision of quantum mechanics mathematics, anything said outside the mathematical formulation is necessarily limited in accuracy.

Also, the precise ontological status of each interpretation remains a matter of philosophical argument. In other words, if we interpret the formal structure X of quantum mechanics by means of a structure Y (via a mathematical equivalence of the two structures), what is the status of Y? This is the old question of saving the phenomena, in a new guise.

Some physicists, for example Asher Peres and Chris Fuchs, argue that an interpretation is nothing more than a formal equivalence between sets of rules for operating on experimental data, thereby implying that the whole exercise of interpretation is unnecessary.

Instrumentalist interpretation

Any modern scientific theory requires at the very least an instrumentalist description that relates the mathematical formalism to experimental practice and prediction. In the case of quantum mechanics, the most common instrumentalist description is an assertion of statistical regularity between state preparation processes and measurement processes. That is, if a measurement of a real-value quantity is performed many times, each time starting with the same initial conditions, the outcome is a well-defined probability distribution agreeing with the real numbers; moreover, quantum mechanics provides a computational instrument to determine statistical properties of this distribution, such as its expectation value.

Calculations for measurements performed on a system S postulate a Hilbert space H over the complex numbers. When the system S is prepared in a pure state, it is associated with a vector in H. Measurable quantities are associated with Hermitian operators acting on H: these are referred to as observables.

Repeated measurement of an observable A where S is prepared in state ψ yields a distribution of values. The expectation value of this distribution is given by the expression

This mathematical machinery gives a simple, direct way to compute a statistical property of the outcome of an experiment, once it is understood how to associate the initial state with a Hilbert space vector, and the measured quantity with an observable (that is, a specific Hermitian operator).

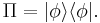

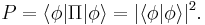

As an example of such a computation, the probability of finding the system in a given state  is given by computing the expectation value of a (rank-1) projection operator

is given by computing the expectation value of a (rank-1) projection operator

The probability is then the non-negative real number given by

By abuse of language, a bare instrumentalist description could be referred to as an interpretation, although this usage is somewhat misleading since instrumentalism explicitly avoids any explanatory role; that is, it does not attempt to answer the question why.

Summary of common interpretations of quantum mechanics

Classification adopted by Einstein

An interpretation (i.e. a semantic explanation of the formal mathematics of quantum mechanics) can be characterized by its treatment of certain matters addressed by Einstein, such as:

- Realism

- Completeness

- Local realism

- Determinism

To explain these properties, we need to be more explicit about the kind of picture an interpretation provides. To that end we will regard an interpretation as a correspondence between the elements of the mathematical formalism M and the elements of an interpreting structure I, where:

- The mathematical formalism M consists of the Hilbert space machinery of ket-vectors, self-adjoint operators acting on the space of ket-vectors, unitary time dependence of the ket-vectors, and measurement operations. In this context a measurement operation is a transformation which turns a ket-vector into a probability distribution (for a formalization of this concept see quantum operations).

- The interpreting structure I includes states, transitions between states, measurement operations, and possibly information about spatial extension of these elements. A measurement operation refers to an operation which returns a value and might result in a system state change. Spatial information would be exhibited by states represented as functions on configuration space. The transitions may be non-deterministic or probabilistic or there may be infinitely many states.

The crucial aspect of an interpretation is whether the elements of I are regarded as physically real. Hence the bare instrumentalist view of quantum mechanics outlined in the previous section is not an interpretation at all, for it makes no claims about elements of physical reality.

The current usage of realism and completeness originated in the 1935 paper in which Einstein and others proposed the EPR paradox.[7] In that paper the authors proposed the concepts element of reality and the completeness of a physical theory. They characterised element of reality as a quantity whose value can be predicted with certainty before measuring or otherwise disturbing it, and defined a complete physical theory as one in which every element of physical reality is accounted for by the theory. In a semantic view of interpretation, an interpretation is complete if every element of the interpreting structure is present in the mathematics. Realism is also a property of each of the elements of the maths; an element is real if it corresponds to something in the interpreting structure. For example, in some interpretations of quantum mechanics (such as the many-worlds interpretation) the ket vector associated to the system state is said to correspond to an element of physical reality, while in other interpretations it is not.

Determinism is a property characterizing state changes due to the passage of time, namely that the state at a future instant is a function of the state in the present (see time evolution). It may not always be clear whether a particular interpretation is deterministic or not, as there may not be a clear choice of a time parameter. Moreover, a given theory may have two interpretations, one of which is deterministic and the other not.

Local realism has two aspects:

- The value returned by a measurement corresponds to the value of some function in the state space. In other words, that value is an element of reality;

- The effects of measurement have a propagation speed not exceeding some universal limit (e.g. the speed of light). In order for this to make sense, measurement operations in the interpreting structure must be localized.

A precise formulation of local realism in terms of a local hidden variable theory was proposed by John Bell.

Bell's theorem, combined with experimental testing, restricts the kinds of properties a quantum theory can have. For instance, Bell's theorem implies that quantum mechanics cannot satisfy local realism.

The Copenhagen interpretation

The Copenhagen interpretation is the "standard" interpretation of quantum mechanics formulated by Niels Bohr and Werner Heisenberg while collaborating in Copenhagen around 1927. Bohr and Heisenberg extended the probabilistic interpretation of the wavefunction proposed originally by Max Born. The Copenhagen interpretation rejects questions like "where was the particle before I measured its position?" as meaningless. The measurement process randomly picks out exactly one of the many possibilities allowed for by the state's wave function in a manner consistent with the well-defined probabilities that are assigned to each possible state. According to the interpretation, the interaction of an observer or apparatus that is external to the quantum system is the cause of wave function collapse, thus according to Heisenberg "reality is in the observations, not in the electron".[8]

Many worlds

The many-worlds interpretation is an interpretation of quantum mechanics in which a universal wavefunction obeys the same deterministic, reversible laws at all times; in particular there is no (indeterministic and irreversible) wavefunction collapse associated with measurement. The phenomena associated with measurement are claimed to be explained by decoherence, which occurs when states interact with the environment producing entanglement, repeatedly splitting the universe into mutually unobservable alternate histories—distinct universes within a greater multiverse.

Consistent histories

The consistent histories interpretation generalizes the conventional Copenhagen interpretation and attempts to provide a natural interpretation of quantum cosmology. The theory is based on a consistency criterion that allows the history of a system to be described so that the probabilities for each history obey the additive rules of classical probability. It is claimed to be consistent with the Schrödinger equation.

According to this interpretation, the purpose of a quantum-mechanical theory is to predict the relative probabilities of various alternative histories (for example, of a particle).

Ensemble interpretation, or statistical interpretation

The Ensemble interpretation, also called the statistical interpretation, can be viewed as a minimalist interpretation. That is, it claims to make the fewest assumptions associated with the standard mathematics. It takes the statistical interpretation of Born to the fullest extent. The interpretation states that the wave function does not apply to an individual system – for example, a single particle – but is an abstract statistical quantity that only applies to an ensemble (a vast multitude) of similarly prepared systems or particles. Probably the most notable supporter of such an interpretation was Einstein:

The attempt to conceive the quantum-theoretical description as the complete description of the individual systems leads to unnatural theoretical interpretations, which become immediately unnecessary if one accepts the interpretation that the description refers to ensembles of systems and not to individual systems.—Einstein in Albert Einstein: Philosopher-Scientist, ed. P.A. Schilpp (Harper & Row, New York)

The most prominent current advocate of the ensemble interpretation is Leslie E. Ballentine, Professor at Simon Fraser University, author of the graduate level text book Quantum Mechanics, A Modern Development. An experiment illustrating the ensemble interpretation is provided in Akira Tonomura's Video clip 1 .[9] It is evident from this double-slit experiment with an ensemble of individual electrons that, since the quantum mechanical wave function (absolutely squared) describes the completed interference pattern, it must describe an ensemble.

de Broglie–Bohm theory

The de Broglie–Bohm theory of quantum mechanics is a theory by Louis de Broglie and extended later by David Bohm to include measurements. Particles, which always have positions, are guided by the wavefunction. The wavefunction evolves according to the Schrödinger wave equation, and the wavefunction never collapses. The theory takes place in a single space-time, is non-local, and is deterministic. The simultaneous determination of a particle's position and velocity is subject to the usual uncertainty principle constraint. The theory is considered to be a hidden variable theory, and by embracing non-locality it satisfies Bell's inequality. The measurement problem is resolved, since the particles have definite positions at all times.[10] Collapse is explained as phenomenological.[11]

Relational quantum mechanics

The essential idea behind relational quantum mechanics, following the precedent of special relativity, is that different observers may give different accounts of the same series of events: for example, to one observer at a given point in time, a system may be in a single, "collapsed" eigenstate, while to another observer at the same time, it may be in a superposition of two or more states. Consequently, if quantum mechanics is to be a complete theory, relational quantum mechanics argues that the notion of "state" describes not the observed system itself, but the relationship, or correlation, between the system and its observer(s). The state vector of conventional quantum mechanics becomes a description of the correlation of some degrees of freedom in the observer, with respect to the observed system. However, it is held by relational quantum mechanics that this applies to all physical objects, whether or not they are conscious or macroscopic. Any "measurement event" is seen simply as an ordinary physical interaction, an establishment of the sort of correlation discussed above. Thus the physical content of the theory has to do not with objects themselves, but the relations between them.[12][13]

An independent relational approach to quantum mechanics was developed in analogy with David Bohm's elucidation of special relativity,[14] in which a detection event is regarded as establishing a relationship between the quantized field and the detector. The inherent ambiguity associated with applying Heisenberg's uncertainty principle is subsequently avoided.[15]

Transactional interpretation

The transactional interpretation of quantum mechanics (TIQM) by John G. Cramer is an interpretation of quantum mechanics inspired by the Wheeler–Feynman absorber theory.[16] It describes quantum interactions in terms of a standing wave formed by retarded (forward-in-time) and advanced (backward-in-time) waves. The author argues that it avoids the philosophical problems with the Copenhagen interpretation and the role of the observer, and resolves various quantum paradoxes.

Stochastic mechanics

An entirely classical derivation and interpretation of Schrödinger's wave equation by analogy with Brownian motion was suggested by Princeton University professor Edward Nelson in 1966.[17] Similar considerations had previously been published, for example by R. Fürth (1933), I. Fényes (1952), and Walter Weizel (1953), and are referenced in Nelson's paper. More recent work on the stochastic interpretation has been done by M. Pavon.[18] An alternative stochastic interpretation was developed by Roumen Tsekov.[19]

Objective collapse theories

Objective collapse theories differ from the Copenhagen interpretation in regarding both the wavefunction and the process of collapse as ontologically objective. In objective theories, collapse occurs randomly ("spontaneous localization"), or when some physical threshold is reached, with observers having no special role. Thus, they are realistic, indeterministic, no-hidden-variables theories. The mechanism of collapse is not specified by standard quantum mechanics, which needs to be extended if this approach is correct, meaning that Objective Collapse is more of a theory than an interpretation. Examples include the Ghirardi-Rimini-Weber theory[20] and the Penrose interpretation.[21]

von Neumann/Wigner interpretation: consciousness causes the collapse

In his treatise The Mathematical Foundations of Quantum Mechanics, John von Neumann deeply analyzed the so-called measurement problem. He concluded that the entire physical universe could be made subject to the Schrödinger equation (the universal wave function). Since something "outside the calculation" was needed to collapse the wave function, von Neumann concluded that the collapse was caused by the consciousness of the experimenter.[22] This point of view was later more prominently expanded on by Eugene Wigner, but remains a view held by very few physicists.[23]

Variations of the von Neumann interpretation include:

- Subjective reduction research

- This principle, that consciousness causes the collapse, is the point of intersection between quantum mechanics and the mind/body problem; and researchers are working to detect conscious events correlated with physical events that, according to quantum theory, should involve a wave function collapse; but, thus far, results are inconclusive.[24][25]

- Participatory anthropic principle (PAP)

-

Main article: Anthropic principle

- John Archibald Wheeler's participatory anthropic principle says that consciousness plays some role in bringing the universe into existence.[26]

Other physicists have elaborated their own variations of the von Neumann interpretation; including:

- Henry P. Stapp (Mindful Universe: Quantum Mechanics and the Participating Observer)

- Bruce Rosenblum and Fred Kuttner (Quantum Enigma: Physics Encounters Consciousness)

Many minds

The many-minds interpretation of quantum mechanics extends the many-worlds interpretation by proposing that the distinction between worlds should be made at the level of the mind of an individual observer.

Quantum logic

Quantum logic can be regarded as a kind of propositional logic suitable for understanding the apparent anomalies regarding quantum measurement, most notably those concerning composition of measurement operations of complementary variables. This research area and its name originated in the 1936 paper by Garrett Birkhoff and John von Neumann, who attempted to reconcile some of the apparent inconsistencies of classical boolean logic with the facts related to measurement and observation in quantum mechanics.

Quantum information theories

Informational approaches subdivide into two kinds[27]

- Information ontologies, such as J. A. Wheeler's "it from bit". These approaches have been described as a revival of immaterialism[28]

- Interpretations where quantum mechanics is said to describe an observer's knowledge of the world, rather than the world itself. This approach has some similarity with Bohr's thinking.[29] Collapse (also known as reduction) is often interpreted as an observer acquiring information from a measurement, rather than as an objective event. These approaches have been appraised as similar to instrumentalism.

The state is not an objective property of an individual system but is that information, obtained from a knowledge of how a system was prepared, which can be used for making predictions about future measurements. ...A quantum mechanical state being a summary of the observer’s information about an individual physical system changes both by dynamical laws, and whenever the observer acquires new information about the system through the process of measurement. The existence of two laws for the evolution of the state vector...becomes problematical only if it is believed that the state vector is an objective property of the system...The “reduction of the wavepacket” does take place in the consciousness of the observer, not because of any unique physical process which takes place there, but only because the state is a construct of the observer and not an objective property of the physical system [30]

Modal interpretations of quantum theory

Modal interpretations of quantum mechanics were first conceived of in 1972 by B. van Fraassen, in his paper “A formal approach to the philosophy of science.” However, this term now is used to describe a larger set of models that grew out of this approach. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy describes several versions:[31]

- The Copenhagen variant

- Kochen-Dieks-Healey Interpretations

- Motivating Early Modal Interpretations, based on the work of R. Clifton, M. Dickson and J. Bub.

Time-symmetric theories

Several theories have been proposed which modify the equations of quantum mechanics to be symmetric with respect to time reversal.[32][33][34] This creates retrocausality: events in the future can affect ones in the past, exactly as events in the past can affect ones in the future. In these theories, a single measurement cannot fully determine the state of a system (making them a type of hidden variables theory), but given two measurements performed at different times, it is possible to calculate the exact state of the system at all intermediate times. The collapse of the wavefunction is therefore not a physical change to the system, just a change in our knowledge of it due to the second measurement. Similarly, they explain entanglement as not being a true physical state but just an illusion created by ignoring retrocausality. The point where two particles appear to "become entangled" is simply a point where each particle is being influenced by events that occur to the other particle in the future.

Branching space-time theories

BST theories resemble the many worlds interpretation; however, "the main difference is that the BST interpretation takes the branching of history to be feature of the topology of the set of events with their causal relationships... rather than a consequence of the separate evolution of different components of a state vector."[35] In MWI, it is the wave functions that branches, whereas in BST, the space-time topology itself branches. BST has applications to Bells theorem, quantum computation and quantum gravity. It also has some resemblance to hidden variable theories and the ensemble interpretation.: particles in BST have multiple well defined trajectories at the microscopic level. These can only be treated stochastically at a coarse grained level, in line with the ensemble interpretation.[35]

Other interpretations

As well as the mainstream interpretations discussed above, a number of other interpretations have been proposed which have not made a significant scientific impact. These range from proposals by mainstream physicists to the more occult ideas of quantum mysticism.

Comparison

The most common interpretations are summarized in the table below. The values shown in the cells of the table are not without controversy, for the precise meanings of some of the concepts involved are unclear and, in fact, are themselves at the center of the controversy surrounding the given interpretation.

No experimental evidence exists that distinguishes among these interpretations. To that extent, the physical theory stands, and is consistent with itself and with reality; difficulties arise only when one attempts to "interpret" the theory. Nevertheless, designing experiments which would test the various interpretations is the subject of active research.

Most of these interpretations have variants. For example, it is difficult to get a precise definition of the Copenhagen interpretation as it was developed and argued about by many people.

| Interpretation | Author(s) | Deterministic? | Wavefunction real? |

Unique history? |

Hidden variables? |

Collapsing wavefunctions? |

Observer role? |

Local? | Counterfactual definiteness? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ensemble interpretation | Max Born, 1926 | Agnostic | No | Yes | Agnostic | No | None | No | No |

| Copenhagen interpretation | Niels Bohr, Werner Heisenberg, 1927 | No | No1 | Yes | No | Yes2 | None | No | No |

| de Broglie-Bohm theory | Louis de Broglie, 1927, David Bohm, 1952 | Yes | Yes3 | Yes4 | Yes | No | None | No | Yes |

| von Neumann interpretation | von Neumann, 1932, Wheeler, Wigner | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Causal | No | No |

| Quantum logic | Garrett Birkhoff, 1936 | Agnostic | Agnostic | Yes5 | No | No | Interpretational6 | Agnostic | No |

| Many-worlds interpretation | Hugh Everett, 1957 | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | None | Yes | No |

| Popper's interpretation[36] | Karl Popper, 1957[37] | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | None | Yes | Yes13 |

| Time-symmetric theories | Yakir Aharonov, 1964 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No |

| Stochastic interpretation | Edward Nelson, 1966 | No | No | Yes | No | No | None | No | No |

| Many-minds interpretation | H. Dieter Zeh, 1970 | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Interpretational7 | Yes | No |

| Consistent histories | Robert B. Griffiths, 1984 | Agnostic8 | Agnostic8 | No | No | No | Interpretational6 | Yes | No |

| Objective collapse theories | Ghirardi-Rimini-Weber, 1986 | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | None | No | No |

| Transactional interpretation | John G. Cramer, 1986 | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes9 | None | No | No |

| Relational interpretation | Carlo Rovelli, 1994 | No | No | Agnostic10 | No | Yes11 | Intrinsic12 | Yes | No |

- 1 According to Bohr, the concept of a physical state independent of the conditions of its experimental observation does not have a well-defined meaning. According to Heisenberg the wavefunction represents a probability, but not an objective reality itself in space and time.

- 2 According to the Copenhagen interpretation, the wavefunction collapses when a measurement is performed.

- 3 Both particle AND guiding wavefunction are real.

- 4 Unique particle history, but multiple wave histories.

- 5 But quantum logic is more limited in applicability than Coherent Histories.

- 6 Quantum mechanics is regarded as a way of predicting observations, or a theory of measurement.

- 7 Observers separate the universal wavefunction into orthogonal sets of experiences.

- 8 If wavefunction is real then this becomes the many-worlds interpretation. If wavefunction less than real, but more than just information, then Zurek calls this the "existential interpretation".

- 9 In the TI the collapse of the state vector is interpreted as the completion of the transaction between emitter and absorber.

- 10 Comparing histories between systems in this interpretation has no well-defined meaning.

- 11 Any physical interaction is treated as a collapse event relative to the systems involved, not just macroscopic or conscious observers.

- 12 The state of the system is observer-dependent, i.e., the state is specific to the reference frame of the observer.

- 13 Caused by the fact that Popper holds both CFD and locality to be true, it is under dispute whether Popper's interpretation can really be considered an interpretation of Quantum Mechanics (which is what Popper claimed) or whether it must be considered a modification of Quantum Mechanics (which is what many Physicists claim), and, in case of the latter, if this modification has been empirically refuted or not. Popper exchanged many long letters with Einstein, Bell etc. about the issue.

See also

Sources

- Bub, J. and Clifton, R. 1996. “A uniqueness theorem for interpretations of quantum mechanics,” Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics 27B: 181-219

- Rudolf Carnap, 1939, "The interpretation of physics," in Foundations of Logic and Mathematics of the International Encyclopedia of Unified Science. University of Chicago Press.

- Dickson, M., 1994, "Wavefunction tails in the modal interpretation" in Hull, D., Forbes, M., and Burian, R., eds., Proceedings of the PSA 1" 366–76. East Lansing, Michigan: Philosophy of Science Association.

- --------, and Clifton, R., 1998, "Lorentz-invariance in modal interpretations" in Dieks, D. and Vermaas, P., eds., The Modal Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers: 9–48.

- Fuchs, Christopher, 2002, "Quantum Mechanics as Quantum Information (and only a little more)." arXiv:quant-ph/0205039

- -------- and A. Peres, 2000, "Quantum theory needs no ‘interpretation’," Physics Today.

- Herbert, N., 1985. Quantum Reality: Beyond the New Physics. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-23569-0.

- Hey, Anthony, and Walters, P., 2003. The New Quantum Universe, 2nd ed. Cambridge Univ. Press. ISBN 0-5215-6457-3.

- Roman Jackiw and D. Kleppner, 2000, "One Hundred Years of Quantum Physics," Science 289(5481): 893.

- Max Jammer, 1966. The Conceptual Development of Quantum Mechanics. McGraw-Hill.

- --------, 1974. The Philosophy of Quantum Mechanics. Wiley & Sons.

- Al-Khalili, 2003. Quantum: A Guide for the Perplexed. London: Weidenfeld & Nicholson.

- de Muynck, W. M., 2002. Foundations of quantum mechanics, an empiricist approach. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers. ISBN 1-4020-0932-1.[38]

- Roland Omnès, 1999. Understanding Quantum Mechanics. Princeton Univ. Press.

- Karl Popper, 1963. Conjectures and Refutations. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. The chapter "Three views Concerning Human Knowledge" addresses, among other things, instrumentalism in the physical sciences.

- Hans Reichenbach, 1944. Philosophic Foundations of Quantum Mechanics. Univ. of California Press.

- Max Tegmark and J. A. Wheeler, 2001, "100 Years of Quantum Mysteries," Scientific American 284: 68.

- Bas van Fraassen, 1972, "A formal approach to the philosophy of science," in R. Colodny, ed., Paradigms and Paradoxes: The Philosophical Challenge of the Quantum Domain. Univ. of Pittsburgh Press: 303-66.

- John A. Wheeler and Wojciech Hubert Zurek (eds), Quantum Theory and Measurement, Princeton: Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-08316-9, LoC QC174.125.Q38 1983.

References

- ^ For a discussion of the provenance of the phrase "shut up and calculate", see [1]

- ^ Vaidman, L. (2002, March 24). Many-Worlds Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics. Retrieved March 19, 2010, from Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/qm-manyworlds/#Teg98

- ^ "Who believes in many-worlds?". Hedweb.com. http://www.hedweb.com/everett/everett.htm#believes. Retrieved 2011-01-24.

- ^ Quantum theory as a universal physical theory, by David Deutsch, International Journal of Theoretical Physics, Vol 24 #1 (1985)

- ^ Three connections between Everett's interpretation and experiment Quantum Concepts of Space and Time, by David Deutsch, Oxford University Press (1986)

- ^ La nouvelle cuisine, by John S. Bell, last article of Speakable and Unspeakable in Quantum Mechanics, second edition.

- ^ A. Einstein, B. Podolsky and N. Rosen, 1935, "Can quantum-mechanical description of physical reality be considered complete?" Phys. Rev. 47: 777.

- ^ http://www.naturalthinker.net/trl/texts/Heisenberg,Werner/Heisenberg,%20Werner%20-%20Physics%20and%20philosophy.pdf

- ^ "An experiment illustrating the ensemble interpretation". Hitachi.com. http://www.hitachi.com/rd/research/em/doubleslit.html. Retrieved 2011-01-24.

- ^ Why Bohm's Theory Solves the Measurement Problem by T. Maudlin, Philosophy of Science 62, pp. 479-483 (September, 1995).

- ^ Bohmian Mechanics as the Foundation of Quantum Mechanics by D. Durr, N. Zanghi, and S. Goldstein in Bohmian Mechanics and Quantum Theory: An Appraisal, edited by J.T. Cushing, A. Fine, and S. Goldstein, Boston Studies in the Philosophy of Science 184, 21-44 (Kluwer, 1996) 1997 arXiv:quant-ph/9511016

- ^ "Relational Quantum Mechanics (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)". Plato.stanford.edu. http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/qm-relational/. Retrieved 2011-01-24.

- ^ For more information, see Carlo Rovelli (1996). "Relational Quantum Mechanics". International Journal of Theoretical Physics 35 (8): 1637. arXiv:quant-ph/9609002. Bibcode 1996IJTP...35.1637R. doi:10.1007/BF02302261.

- ^ David Bohm, The Special Theory of Relativity, Benjamin, New York, 1965

- ^ [2]. For a full account [3], see Q. Zheng and T. Kobayashi, 1996, "Quantum Optics as a Relativistic Theory of Light," Physics Essays 9: 447. Annual Report, Department of Physics, School of Science, University of Tokyo (1992) 240.

- ^ "Quantum Nocality - Cramer". Npl.washington.edu. http://www.npl.washington.edu/npl/int_rep/qm_nl.html. Retrieved 2011-01-24.

- ^ Nelson,E. (1966) Derivation of the Schrödinger Equation from Newtonian Mechanics, Phys. Rev. 150, 1079-1085

- ^ M. Pavon, “Stochastic mechanics and the Feynman integral”, J. Math. Phys. 41, 6060-6078 (2000)

- ^ Roumen Tsekov (2009). "Bohmian Mechanics versus Madelung Quantum Hydrodynamics". arXiv:0904.0723 [quant-ph].

- ^ "Frigg, R. GRW theory" (PDF). http://www.romanfrigg.org/writings/GRW%20Theory.pdf. Retrieved 2011-01-24.

- ^ "Review of Penrose's Shadows of the Mind". Thymos.com. http://www.thymos.com/mind/penrose.html. Retrieved 2011-01-24.

- ^ von Neumann, John. (1932/1955). Mathematical Foundations of Quantum Mechanics. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Translated by Robert T. Beyer.

- ^ Zvi Schreiber (1995). "The Nine Lives of Schroedinger's Cat". arXiv:quant-ph/9501014 [quant-ph].

- ^ Dick J. Bierman and Stephen Whitmarsh. (2006). Consciousness and Quantum Physics: Empirical Research on the Subjective Reduction of the State Vector. in Jack A. Tuszynski (Ed). The Emerging Physics of Consciousness. p. 27-48.

- ^ C. M. H. Nunn et. al. (1994). Collapse of a Quantum Field may Affect Brain Function. Journal of Consciousness Studies. 1(1):127-139.

- ^ "- The anthropic universe". Abc.net.au. 2006-02-18. http://www.abc.net.au/rn/scienceshow/stories/2006/1572643.htm. Retrieved 2011-01-24.

- ^ Information, Immaterialism, Instrumentalism: Old and New in Quantum Information. Christopher G. Timpson

- ^ Timpson,Op. Cit.: "Let us call the thought that information might be the basic category from which all else flows informational immaterialism."

- ^ "Physics concerns what we can say about nature". (Niels Bohr, quoted in Petersen, A. (1963). The philosophy of Niels Bohr. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 19(7):8–14.)

- ^ Hartle, J. B. (1968). Quantum mechanics of individual systems. Am. J. Phys., 36(8):704– 712.

- ^ "Modal Interpretations of Quantum Mechanics (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)". Science.uva.nl. http://www.science.uva.nl/~seop/entries/qm-modal/. Retrieved 2011-01-24.

- ^ Aharonov, Y. and Vaidman, L. "On the Two-State Vector Reformulation of Quantum Mechanics." Physica Scripta, Volume T76, pp. 85-92 (1998).

- ^ Wharton, K. B. "Time-Symmetric Quantum Mechanics." Foundations of Physics, 37(1), pp. 159-168 (2007).

- ^ Wharton, K. B. "A Novel Interpretation of the Klein-Gordon Equation." Foundations of Physics, 40(3), pp. 313-332 (2010).

- ^ a b Sharlow, Mark; "What Branching Spacetime might do for Phyiscs" p.2

- ^ Marie-Christine Combourieu: Karl R. Popper, 1992: About the EPR controversy. Foundations of Physics 22:10, 1303-1323

- ^ Karl Popper: The Propensity Interpretation of the Calculus of Probability and of the Quantum Theory. Observation and Interpretation. Buttersworth Scientific Publications, Korner & Price (eds.) 1957. pp 65–70.

- ^ de Muynck, Willem M (2002). Foundations of quantum mechanics: an empiricist approach. Klower Academic Publishers. ISBN 1402009321. http://books.google.com/?id=k3rUe8XVjJUC&printsec=frontcover&dq=an+empiricist+approach#v=onepage&q=&f=false. Retrieved 2011-01-24.

Further reading

Almost all authors below are professional physicists.

- David Z Albert, 1992. Quantum Mechanics and Experience. Harvard Univ. Press. ISBN 0674741129.

- John S. Bell, 1987. Speakable and Unspeakable in Quantum Mechanics. Cambridge Univ. Press, ISBN 0-521-36869-3. The 2004 edition (ISBN 0-521-52338-9) includes two additional papers and an introduction by Alain Aspect.

- Dmitrii Ivanovich Blokhintsev, 1968. The Philosophy of Quantum Mechanics. D. Reidel Publishing Company. ISBN 9027701059.

- David Bohm, 1980. Wholeness and the Implicate Order. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-7100-0971-2.

- Adan Cabello (15 November 2004). "Bibliographic guide to the foundations of quantum mechanics and quantum information". arXiv:quant-ph/0012089 [quant-ph].

- David Deutsch, 1997. The Fabric of Reality. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 014027541X; ISBN 0713990619. Argues forcefully against instrumentalism. For general readers.

- Bernard d'Espagnat, 1976. Conceptual Foundation of Quantum Mechanics, 2nd ed. Addison Wesley. ISBN 081334087X.

- --------, 1983. In Search of Reality. Springer. ISBN 0387113991.

- --------, 2003. Veiled Reality: An Analysis of Quantum Mechanical Concepts. Westview Press.

- --------, 2006. On Physics and Philosophy. Princeton Univ. Press.

- Arthur Fine, 1986. The Shaky Game: Einstein Realism and the Quantum Theory. Science and its Conceptual Foundations. Univ. of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226249484.

- Ghirardi, Giancarlo, 2004. Sneaking a Look at God’s Cards. Princeton Univ. Press.

- Gregg Jaeger (2009) Entanglement, Information, and the Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics. Springer. ISBN 9783540921271.

- N. David Mermin (1990) Boojums all the way through. Cambridge Univ. Press. ISBN 0521388805.

- Roland Omnes, 1994. The Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics. Princeton Univ. Press. ISBN 0691036691.

- --------, 1999. Understanding Quantum Mechanics. Princeton Univ. Press.

- --------, 1999. Quantum Philosophy: Understanding and Interpreting Contemporary Science. Princeton Univ. Press.

- Roger Penrose, 1989. The Emperor's New Mind. Oxford Univ. Press. ISBN 0-198-51973-7. Especially chpt. 6.

- --------, 1994. Shadows of the Mind. Oxford Univ. Press. ISBN 0-19-853978-9.

- --------, 2004. The Road to Reality. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. Argues that quantum theory is incomplete.

External links

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy:

- "Bohmian mechanics" by Sheldon Goldstein.

- "Collapse Theories." by Giancarlo Ghirardi.

- "Copenhagen Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics" by Jan Faye.

- "Everett's Relative State Formulation of Quantum Mechanics" by Jeffrey Barrett.

- "Many-Worlds Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics" by Lev Vaidman.

- "Modal Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics" by Michael Dickson and Dennis Dieks.

- "Quantum Entanglement and Information" by Jeffrey Bub.

- "Quantum mechanics" by Jenann Ismael.

- "Relational Quantum Mechanics" by Federico Laudisa and Carlo Rovelli.

- "The Role of Decoherence in Quantum Mechanics" by Guido Bacciagaluppi.

- Willem M. de Muynck, Broad overview of the realist vs. empiricist interpretations, against oversimplified view of the measurement process.

- Schreiber, Z., "The Nine Lives of Schrodinger's Cat." Overview of competing interpretations.

- Interpretations of quantum mechanics on arxiv.org.

- The many worlds of quantum mechanics.

- Erich Joos' Decoherence Website.

- Quantum Mechanics for Philosophers. Argues for the superiority of the Bohm interpretation.

- Hidden Variables in Quantum Theory: The Hidden Cultural Variables of their Rejection.

- Numerous Many Worlds-related Topics and Articles.

- Relational Approach to Quantum Physics.

- Theory of incomplete measurements. Deriving quantum mechanics axioms from properties of acceptable measurements.

- Alfred Neumaier's FAQ.

- Measurement in Quantum Mechanics FAQ.